Overview of the German Education System

By Tiffany Cherry, Upper Merion Area School District; Pam Kilgore, Washington School District; Jennifer Lowman, Cheltenham School District; Kelly White, Wyalusing Area School District

In March 2025, a group of 14 school board members, state legislatures, educators, and PSBA staff traveled to the German state of North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW) as part of PSBA’s second International Education Study Group. In just five days, we visited five schools, including primary and secondary schools, as well as the Parliament and the Ministry of Schools and Education in Düsseldorf, the capital of NRW, Düsseldorf’s municipal office of education, a technical training center at a Mercedes-Benz plant, a teacher training program at the University of Siegen, a Center for Practical Teacher Training in Aachen, and a Euregional Center for Digital Education.

It was a whirlwind tour through NRW’s school system which provided us with an opportunity to speak with politicians, educators, administrators, students, professors and student teachers about the strengths of and challenges faced by NRW’s public education system. Before we jump into what we learned and questions we still have, we will start with a broad overview of the German education system, and provide some more details about NRW’s system, to provide context to our observations.

Quick Summary of the German Education System

- Similar to the United States, Germany has a decentralized federal public education system. Its 16 federal states (Bundesländer or Länder) are primarily responsible for education policy and administration.

- The German education system has five main stages: early childhood education, primary school, secondary school, higher education and continuing education.

- The German school system is unique from other European Union (EU) countries and the United States because it sorts students into different educational paths early on (either from grade 4 or grade 6 depending upon the state).

- There is a significant focus on vocational education and training (VET) which is supported by extensive collaboration between private businesses, local and state governments, secondary schools, and chambers of commerce.

- Germany offers free or affordable higher education to both local and international students.

Source: Adapted from German Education System (Haxhiavdyli, December 18, 2024)

Overview

Public school governance in Germany is decentralized and shaped by its federal structure. The 16 federal states (Bundesländer or Länder) are primarily responsible for education policy and school administration. The Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) is mainly responsible for:

- Higher education and research

- National education standards coordination

- International cooperation

While the federal government does not control K–12 public schooling, it plays a coordinating and funding support role, particularly in science, research and innovation.

Public schools in Germany are free for all students. Each state government funds the majority of public school costs, including:

- Teacher salaries (most teachers are civil servants paid directly by the state)

- Curriculum development

- Educational administration

States allocate funds based on their own education budgets, which vary depending on the state’s size, wealth and political priorities. The states fund their public schools primarily through a share of national tax revenues, along with some state-specific taxes and transfers.

Municipalities, or local governments, are responsible for the physical infrastructure and day-to-day operational needs, including:

- Building and maintaining school facilities

- Providing furniture, supplies and IT equipment

- School transportation and lunches (in some cases)

Municipalities receive funding from local taxes (like property and business taxes), some of which is shared with or transferred from the state.

Each state is responsible for its own education policies, though they follow general national guidelines. Each state sets the curriculum for its schools, but individual schools have autonomy over instructional methods. Teachers unions in Germany play a significant role in advocating for salaries, working conditions and education policy.

The percentage of students who attend private schools in Germany is less than it is in the United States (about 9% of students attend private schools in Germany compared to 11.8% in the U.S.). Homeschooling is illegal in Germany with a few very limited exceptions. Charter schools and cyber charter schools do not exist in Germany.

Compulsory Education

It is a fundamental right of every child in Germany to receive an education. As part of compulsory education, all children in Germany must start school once they reach the age of 6 up until they complete nine years of full-time schooling (15 years old) at a Gymnasium or 10 years of full-time schooling (16 years old) at other general education schools. After general compulsory schooling, those who do not continue their education at a full-time general or vocational upper secondary school must still attend part-time schooling until age 18.

From grades 1-4, children attend primary school, known as Grundschule, which is similar to the elementary school level in the United States. (In Germany, Kindergarten is considered preschool, it is provided privately, and attendance is not required.) Children then go to secondary school from grade 5 to the end of Secondary Level I. The types of secondary schools that children have the option of attending vary from state to state and municipality to municipality. More information about NRW’s specific school configuration can be found below.

Students must then attend either a vocational college or the sixth-form style gymnasiale Oberstufe until the end of the school year in which they reach 18 or graduate from a full-time secondary education program at the Secondary Level II. Those starting a vocational training program before reaching the age of 21 must continue to attend until it finishes. (Source: The School System in Nordrhein-Westfalen Explained Quickly and Easily, September 2024, from the Ministerium für Schule und Bildung des Landes Nordrhein-Westfalen)

Public School Structure in North Rhine-Westphalia

- Kindergarten (Preschool): Ages 3–6 (not mandatory)

- Grundschule (Primary School): Grades 1-4 (ages 6-10)

- Secondary Education:

- After grade 4, students are typically placed into one of several school types based on academic performance and teacher recommendations (parents in NRW can override that placement recommendation):

- Hauptschule (Grades 5-9/10): Focus on vocational and general education

- Realschule (Grades 5-10): Broader academic education, leads to mid-level jobs or vocational training

- Gymnasium (Grades 5-12/13): Academic track leading to the Abitur (university entrance qualification)

- After grade 4, students are typically placed into one of several school types based on academic performance and teacher recommendations (parents in NRW can override that placement recommendation):

- Gesamtschule: Comprehensive school combining all three tracks (unique to NRW and closest to traditional U.S. high school)

- Vocational Education/Dual System: Combines apprenticeships in companies with part-time schooling (Berufsschule)

- Higher Education: Universities, Fachhochschulen (Universities of Applied Sciences)

Primary and Secondary Education in North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW)

In NRW, there are 5,404 schools, 212,900 teachers, and nearly 2.5 million students. Public schools in NRW are, for the most part, maintained jointly by the state and municipalities or administrative districts. The Ministry of School and Education (Ministerium für Schuleund Bildung), which is located in Düsseldorf, supervises the entire school system for the federal state of NRW. There are five district governments (Bezirksregierungen) responsible for the supervision of secondary schools, comprehensive schools, grammar schools, vocational colleges as well as schools for students with special needs (Förderschulen), and 53 state education authorities (Schulämter), which are responsible for the supervision of elementary schools, Hauptschulen and certain Förderschulen.

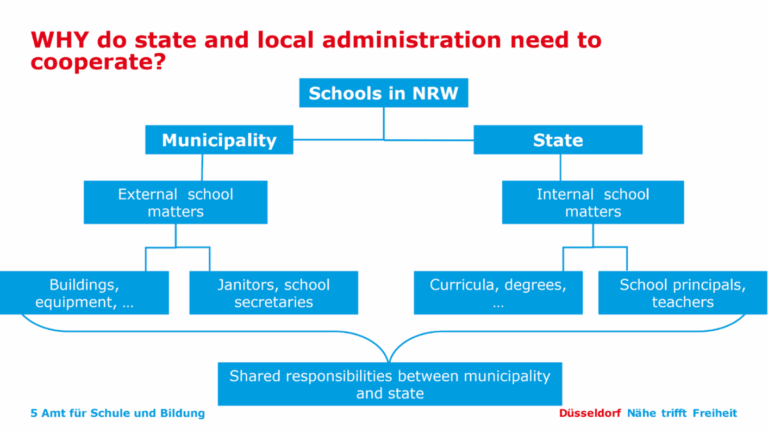

As noted above, the state of NRW bears the cost of paying for teaching staff, and other staff (e.g., social workers, custodians, secretaries) are funded by the local authorities. The chart below provides an overview of this governance structure in NRW.

For all of these layers of governance, schools each seem to have their own unique cultures and characteristics. At a building level, school governance feels quite decentralized. The schools we visited each had their own missions and visions about education.

For example, GHS Korschenbroich Hauptschule, a general secondary school located about 12 miles outside of Dusseldorf, prides itself on being a small, progressive school (215 total students in grades 5-10 with 27-30 teachers and social workers) that meets the diverse needs of its students who come from 31 different counties. Thirty-one students at GHS Korschenbroich have refugee status and are learning German. This small school does everything from providing inclusive education to students with learning disabilities, to offering homework tutoring for their students in grades 5 and 6, to providing a wide range of electives and opportunities for internships to older students.

Gymnasium Korschenbroich, which is right down the road from GHS Korschenbroich, has 1,000 students between the ages of 10 and 19, 80 teachers, and a completely different approach to education than GHS Korschenbroich. The Gymnasium offers three different languages for students to study, an opportunity to take part in several different international student exchanges, including one with Anchorage, AL, and a focus on science competitions as well as music, arts and theater.

We also visited Gustav-Heinemann-Gesamtschule (GHG) in Alsdorf, a town of about 48,940 people which is 42 miles south of Dusseldorf. GHG offers yet a third type of secondary schooling option – a comprehensive high school with 1,300 students in grades 5-12. Not surprisingly, this school has elements of both a Hauptschule and Gymnasium.

Diversity and equity are very important values at GHG. Students from 19 different countries attend the school and 18% of the students have an immigration background. GHG offers “International classes” for newly arrived students who speak no German at all. When we visited, the school had 40 students from Ukraine, Syria, Iran, Iraq, Bosnia and several other countries in one International class. The school also provides co-taught classes for students with disabilities and focuses on inclusion. It offers robust international exchange programs through Erasmus, an EU program, as well as facilitating an exchange program with a school in Namibia. In addition to GHG, Alsdorf also has a Gymnasium and two Realschulen, so there are several different secondary school options for children in that area.

School building administration is very leanly staffed. Headmasters (as principals are called) and their assistants teach at the school. (For instance, the headmaster at GHG is also a physical education and math teacher.) Other teachers take on additional roles such as IT coordinator or inclusion coordinator.

There are several other facets of the public education system in NRW that we learned about which are specific to that state. These include:

- Parental choice: In NRW, parents can determine their child’s secondary school placement. Different from other German states, parents in NRW can override teacher placement recommendations regarding which secondary school would best meet their child’s needs. Several educators told us that more parents are choosing to send their children to Gymnasium rather than Hauptschule or Realschule because they think attending university should be their goal. However, children who then struggle with the academic rigor of a Gymnasium often end up attending a different school in grades 6 or 7.

- Integration efforts: In the past 10 years, NRW has received waves of refugees, asylum seekers and immigrants from Syria, Afghanistan, Turkey, Romania, Ukraine and elsewhere. About 100,000 newly immigrated students currently attend schools in NRW.

A major focus of NRW’s government is the integration of these newly immigrated students into the North Rhine-Westphalian school system. NRW established Municipal Integration Centers (MIC) in 2013. There are now 54 MICs supported jointly by the state Ministry of Integration and Ministry of Schools and Education in NRW. The state provides teachers to staff the MICs, and one of their tasks is to screen new students to advise on the best school placement for them.

Schools provide different types of German-language support to newly arrived students depending upon their needs. Some students from war-torn countries may have never attended school in their country of origin, and they may first need to learn basic literacy skills in their language of origin before learning German. Several educators we met also spoke of the challenges teaching German to students whose language of origin is Arabic or another non-Romance language.

- Embrace of multilingualism: At least 45% of all students in NRW have a multilingual background. Over 106,000 students in NRW take part in “heritage language lessons” or Herkunftssprachlicher Unterricht (HSU). A total of 30 different languages are taught in over 7,300 learning groups. The most common languages are Turkish, Arabic, Russian, Polish, Italian and Greek.

Students with an international family history learn the language that plays a major role in their family (“heritage language,” “language of origin” or “family language”). Some of the goals of teaching students to master their heritage language include supporting their ability to learn German as a second language, providing a way to involve families more in their child’s education, and strengthening the identity and intercultural competencies of all students.

- Availability of Gesamtschule: NRW is currently the only state in Germany which offers Gesamtschule. Gesamtschule is a comprehensive high school which is the German secondary school closest to a typical high school in the United States. The school has classes for students at all different ability levels and interests; there are tracks for students headed to university, vocational training and other work options.

- Teacher education and training: Teacher education and training in German is defined and regulated by each federal state’s Lehrerausbildungsgesetz (legal provisions for teacher education and training). Aspiring teachers must complete a university-level education program, typically lasting between four and six semesters, specializing in a specific subject or combination of subjects. This is followed by a practical phase of at least two years, involving supervised teaching in a school setting and mentoring by experienced educators. Successful completion of both phases results in the Lehramt, the teaching qualification. In order to prepare students for working in diverse classroom settings, NRW teacher education curriculum also includes:

- A module on teaching German for Students with an Immigration Background (DSSZ)

- Studies on:

- Inclusive pedagogical concepts

- Heterogeneity as the norm

- Media literacy and digitalization in schools (contents and methods)

This demanding process emphasizes both subject matter expertise and pedagogical skills, aiming to produce highly qualified teachers. However, the long training period and relatively high entry requirements (applicants to teacher training programs must have very high grades) can create shortages in certain subject areas, particularly in science and mathematics.

Integration through Education

“It is firmly anchored in the North Rhine-Westphalia Education Act to provide all young people in our schools with the educational opportunities that match their abilities. For newly immigrated students, the focus is on promoting German so that they can participate fully in lessons as soon as possible.”

-NRW Education Minister Dorothee Feller

In recent decades, Germany has received the second largest number of refugees in Europe. Refugees from Syria, Afghanistan, Turkey and most recently, Ukraine have found haven in Germany. Presently, almost 100,000 newly immigrated students are enrolled in NRW schools. Notably, NRW hosts the largest number of Ukrainian refugees of any German state.

Methods of integrating German language learners are evolving in real-time. NRW Ministry of Education staff with backgrounds in education, policy and, in some cases, lived immigrant experience, help to shape policy and practice. Guided by principles outlined in The Participation and Integration Act first passed in 2012 by NRW, programs are designed to help schools promote “mutual openness and tolerance.”

“The school promotes the integration of students whose native language is not German by offering opportunities to learn German. In doing so, it respects and promotes the ethnic, cultural, and linguistic identity (native language) of these students.”

-Section 2, Paragraph 10 of the School Act

Policies for the integration of refugees promote engagement and success in a family’s new community. State-run Municipal Integration Centers are located within each district or independent city and provide newly arrived individuals access to resources and support. These Centers work closely with schools, social institutions and authorities and serve as a vital resource for refugee families. Among the services rendered at these centers, children are assessed by educators to determine specific educational needs.

Children of school-age arriving without sufficient German language skills benefit from what is known as initial support. The primary goal of initial support is learning the German language. The faster German is learned, the more likely newly arrived students are to fully participate in lessons. Within this framework, students are placed in one of three learning formats:

- Internal differentiation, i.e., within the framework of full participation in regular classes;

- Partial external differentiation, i.e., by attending a separate learning group and partially participating in regular classes or;

- Complete external differentiation, i.e., in separate learning groups.

This introduction to German language and learning for newly arrived students typically lasts two years; however, upper primary or secondary learners with little-to-no literacy upon arrival benefit from a third year of support for German language learning.

German language skills are recognized as essential to successful integration into German society; At the same time, the NRW Education Ministry promotes advancing skills in a student’s native language. Mastering the first language supports learning of other languages, problem-solving skills, and strengthens identity and intercultural competencies of all students. These heritage language lessons (HSU) engage over 100,000 students in 30 languages.

“The state recognizes multilingualism as an important potential for the cultural, scientific and economic development of North Rhine-Westphalia and for the promotion of equal opportunities for participation in education within the meaning of this law.”

-Section 10, paragraph 1 of the Participation and Integration Act

Engaging families in education is promoted with the Rucksack School program, assisting families with multilingualism. As a complement to in-school HSU, this program encourages parents of the youngest learners to pass on school content in their family language. Parents are trained once a week by parent support workers, building another level of community for families.

“The parent support workers are indispensable players in supporting families and make a significant contribution to successful integration and language development… .”

-Jennifer Eicker, member of the parent education team at the Essen Youth Welfare Office

Integration through Education: Policies in Practice

The systems determining the structure of integration through education in NRW were made real as we visited each level within the framework. The state of NRW provides the legislative mandates and support for integration in schools. The Ministry of Education provides teacher training, language learning specialists and curricula for the integration of immigrant and refugee students. Finally, the schools implement these policies and tools. At all levels, legislators, experts, teachers, staff and administrators spoke with passion for honoring learners through inclusion and integration. By walking through halls and sitting in classrooms, we were able to engage with the people behind the numbers, policies and statistics seen on screens days earlier.

Among these, Malmedyer Straße Elementary School provided a memorable, in-depth look at its school community. This Elementary School prioritizes social, emotional learning and support for the entire school community. This includes incorporation of small-group teaching and team teaching, both allowing for more attention to students’ individual needs. In addition to these daily classroom practices, trauma-informed practices available to students include quiet spaces adjacent to each room, a community quiet room for rest and calm, and twice weekly visits from a therapy dog.

Integration through Education: Challenges

Education can be incredibly rewarding and incredibly difficult. Educating children who speak a different language, have suffered trauma or lack any formal education are compounding challenges. Resources are outpaced by the increasing needs of communities.

Recognizing the benefit of early education, childcare and preschool (kindergarten) programs are largely subsidized by the state. However, availability has not caught up with demand, and these programs frequently have waiting lists.

Professionals trained in special education, multilingualism, counseling and other specialized supports are in short supply, and the number of students pursuing a career in education is declining.

As is common the world over, schools in NRW would benefit from additional resources. But the schools we visited were also replete with practitioners who provide the most essential support for students – caring adults. That is not to say the integration model does not have its detractors. Some see the influx of immigrant and refugee families as a drain on limited resources. But for the time being, the integration model and its policies continue to garner wide support in NRW.

Understanding Education in North Rhine-Westphalia: Funding, Teacher Training and Salaries

North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW), the most populous state in Germany, plays a central role in shaping the country’s educational landscape. With a diverse population and a commitment to equal access to quality education, NRW’s school system is built on solid foundations – yet it faces some challenges. To fully appreciate how education functions in this region, it’s important to explore how schools are funded, how teachers are trained and what kind of salaries educators receive.

Teacher Training: A Rigorous Pathway

Becoming a teacher in NRW – and throughout Germany – is a demanding process that emphasizes both academic knowledge and real-world classroom skills. Future teachers first enroll in a university degree program in their chosen subjects (e.g., math, languages, science). This academic phase typically lasts four to five years and includes courses in pedagogy, psychology and education theory.

After university, candidates enter a two-year practical phase. They work in real schools under supervision, gradually taking on more teaching responsibilities. This hands-on experience is supported by regular feedback and mentoring. Upon successfully completing both phases, candidates earn the Lehramt, the official teaching qualification.

This structured process ensures that teachers are well-prepared, but it also takes time and dedication. As a result, there is a nationwide shortage of qualified teachers in certain subjects – especially in STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics).

To keep up with changing educational demands, NRW encourages lifelong learning for teachers. The state offers a range of professional development programs (such as Lehrerfortbildung NRW) focusing on modern teaching methods, digital tools, inclusive education and intercultural competence. This support is crucial in helping teachers stay motivated and adapt to the needs of diverse student populations.

Teacher pay in NRW is generally considered fair and competitive, especially compared to other public service jobs. However, it varies based on several factors:

- Experience and qualifications: Teachers earn more as they gain experience and take on additional roles.

- Position: School principals and administrative leaders receive higher pay due to their increased responsibilities.

- Type of school and contract: Teachers in public schools follow salary scales defined by collective agreements (Tarifverträge) between unions and the government. Private school salaries may differ.

Despite its strong foundation, NRW’s education system is not without its flaws. Regional funding gaps, teacher shortages and the pressures of modern classroom environments all need attention. Some key areas for improvement include:

- Reforming the funding model to ensure more equal distribution of resources between rich and poor districts

- Shortening or streamlining the teacher training pipeline without compromising quality, especially to attract more young people into high-demand subjects

- Enhancing support for teachers through better working conditions, mental health services and opportunities for advancement

Education in NRW reflects both the strengths and complexities of the broader German system. With a dual funding structure, a well-regarded teacher training pathway and a fair salary framework, the state is well-positioned to deliver quality education. However, to ensure that every child – regardless of background – receives the same opportunities, further reforms are necessary.

Beyond the Classroom: Parents and Community as Educational Partners

In NRW, parent involvement plays an important part in children’s education. Unlike educational systems that position parents as passive recipients of educational services, NRW has created multiple channels and opportunities through which families directly influence their children’s education. The North Rhine-Westphalia School Act (Schulgesetz NRW) mandates structured parent participation through formal bodies with significant decision-making authority.

The foundation begins in the classroom with the election of class parent representatives (Klassenelternsprecher) at the beginning of each school year. These representatives collectively form the school’s parents’ council (Schulpflegschaft) – a legally recognized body with statutory rights to consultation and participation in school decisions.

A typical Schulpflegschaft at a comprehensive school might include 30-35 members – one parent representative from each class – plus an executive committee elected from among the representatives. These councils generally meet monthly and address issues ranging from teaching methods to facilities improvements.

What distinguishes the NRW model is the actual power vested in these parent councils. Their authority includes:

- Consultation rights on curriculum changes, school scheduling and teaching materials

- Approval authority for optional school activities and certain budget allocations

- Representation on hiring committees for new staff members

- Participation in disciplinary proceedings

- Formal channels to raise concerns to district and state education authorities

The council’s influence culminates in the School Conference (Schulkonferenz), where parents hold one-third of the votes alongside teachers and, in secondary schools, students. This tripartite governing body makes the most significant decisions affecting school life.

This partnership model extends beyond formal governance structures into a broader educational ecosystem where municipalities, businesses and civil society organizations all play important roles. In municipalities across the state, youth centers (Jugendzentren) and after-school programs (Nachmittagsbetreuung) offer everything from homework support to music, arts and sports – which is particularly valuable for families in which both parents work full-time.

Municipal support extends to providing facilities, funding specialized staff positions and ensuring schools are integrated into community planning. This integration reflects the state’s commitment to education as a community-wide responsibility.

NRW’s approach to parent and community involvement represents one of the more progressive models in Germany. While all German states maintain some form of structured parent participation, NRW has been particularly focused on creating municipal education networks that connect schools with local resources. This approach differs notably from the more traditional models found in southern states where parent associations typically have more limited decision-making authority.

As NRW looks toward the educational challenges of coming decades, several priorities have emerged:

- Reforming funding models to better distribute resources across socioeconomically diverse communities

- Making teaching careers more attractive, particularly in understaffed fields

- Improving digital integration while ensuring technology enhances rather than distracts from fundamental learning

- Balancing preservation of traditional educational strengths with adaptation to changing social and economic realities

While the formal structures are impressive, day-to-day communication forms the backbone of parent involvement. NRW schools typically offer:

- Biannual parent-teacher conferences (Elternsprechtage)

- Regular individual consultations with teachers

- Thematic information evenings on topics ranging from curriculum changes to digital literacy

- Digital communication platforms connecting parents and schools

Many schools have embraced digital tools to enhance this communication, with apps and online portals providing real-time updates on student progress, upcoming events and school announcements.

The NRW approach demonstrates that meaningful parent involvement requires more than occasional volunteering or fundraising events. It necessitates systematic integration of parent voices at all levels of decision-making, creating a genuine educational community where families and schools work as partners.

For families in NRW, education is not something that happens exclusively in classrooms – it is a collaborative endeavor, with parent councils serving as the formal bridge between home, school and community.

In an era where education systems worldwide seek to become more responsive and inclusive, the structures developed in this German state offer valuable insights into creating sustainable, meaningful parent engagement – a model where parents don’t just entrust their children to schools but actively shape the institutions that serve them.

NRW Education at a Glance

Population: 18 million residents

School types: Primary schools (Grundschulen), followed by Hauptschulen, Realschulen, Gymnasien, and comprehensive schools (Gesamtschulen)

Special features: Strong emphasis on comprehensive schools, expanding all-day education, inclusive approaches for special needs students

Teacher training: Dual-phase system with university education followed by practical training (typically six years total)

Parent involvement: Structured participation through Schulpflegschaft (parents’ council) and Schulkonferenz (school conference) with voting rights on educational decisions

Community resources: Youth centers (Jugendzentren), after-school programs and traditional clubs (Vereine) that complement formal education

Key challenges: Resource disparities between municipalities, teacher shortages in STEM subjects, integration of diverse student populations

Recent initiatives: Digital infrastructure investment, language support programs, expanded vocational education partnerships

The Role of Municipalities in Education in North Rhine-Westphalia

In Germany’s federated education system, responsibility for schools is distributed across multiple governmental levels, creating a complex but effective partnership between state authorities and local municipalities. This arrangement is particularly well-developed in NRW, where municipalities are shaping educational environments while respecting the state’s curricular authority.

Germany’s approach to educational governance follows what experts call the “dual system” (Duale System), which divides educational responsibilities between two primary stakeholders – state and municipalities. This division creates a balanced approach to education. The state ensures educational consistency across regions, while municipalities can respond to local needs and community priorities.

The State (Land) which is responsible for educational policy and curriculum development; teacher training, qualification, employment, and salaries; academic standards and quality control; and school supervision and inspection.

Municipalities (Kommunen) are responsible for physical infrastructure (school buildings, facilities, equipment), non-teaching staff (administrators, janitors, technical support), transportation systems, and extracurricular and support programs.

In NRW, municipalities function as Schulträger (school providers), a role codified in the state’s School Act. As Schulträger, local governments are legally obligated to:

- Establish and maintain school buildings – This includes construction, renovation and ongoing maintenance of all public-school facilities. The municipality determines architectural design, allocates space for specialized rooms (science labs, gymnasiums, etc.), and ensures compliance with building codes and safety standards.

- Provide equipment and learning materials – While the state determines which textbooks and curricula will be used, municipalities supply the physical resources necessary for implementation, including furniture, technology infrastructure, laboratory equipment and library materials.

- Employ administrative and support staff – Municipal authorities hire and manage nonpedagogical personnel, creating an important distinction from teaching staff, who are state employees.

- Develop school transportation networks – In rural areas particularly, municipalities coordinate bus routes and transportation subsidies to ensure all students can access education.

- Establish school district boundaries – Within parameters set by state regulations, municipalities determine which schools serve which neighborhoods, though school choice policies have somewhat diminished the importance of strict districting.

In NRW, municipalities collectively spend approximately €4.2 billion annually on school infrastructure and operations, representing roughly 15% of total municipal budgets on average. This substantial investment is supported through local tax revenues, state grants and subsidies, federal infrastructure programs, and European Union development funds.

What distinguishes NRW from some other German states is the expanded role municipalities have taken in educational support systems. NRW municipalities frequently go beyond their mandated responsibilities to provide. Following education reforms in the early 2000s, NRW municipalities became central providers of Offene Ganztagsschulen (open-all-day schools) programs. These after-school offerings, which now serve approximately 330,000 students across the state, are organized and largely funded at the municipal level, with state subsidies covering only a portion of costs.

Each municipality in NRW maintains a Schulausschuss (school board or committee) as part of its democratic governance structure. These committees typically include elected municipal council representatives, school administrators, parent representatives, student representatives (in secondary education) and community stakeholders.

NRW’s approach to municipal educational responsibility represents a distinctive model of educational federalism that balances standardization with local responsiveness. By giving municipalities significant authority over educational environments while preserving state control of curriculum and teaching, the system creates schools that can both maintain consistent academic standards and reflect community priorities.

About the authors

School director Tiffany Cherry has served on the Upper Merion Area School Board since 2021. She chairs the board’s Policy and Equity Committee and serves as its PSBA liaison. Upper Merion is a suburban district located in Montgomery County, part of the Greater Philadelphia Metropolitan area. District enrollment includes 4,500 public school students and is home to five elementary schools (grades K-4), one middle school (grades 5-8), and one high school (grades 9-12). More information about the district can be found at www.UMASD.org.

School director Pam Kilgore has served on the Washington School District (WSD) school board since December 2023. She currently serves on the Education Committee and as her district’s PSBA liaison. WSD serves 15,000 residents across two municipalities, the City of Washington and the Borough of East Washington. The student population of 1,400 students reflects a diverse demographic composition that is 43% white, 26% African American, 21% multiracial, 5% Hispanic, and less than 1% Asian or Indigenous. Approximately 30% of our students receive special education services. Additionally, the district serves 100 students in grades K-12 virtually through the Prexie Cyber Academy. High school students may also attend programs at the Western Area Career and Technical Center. Because many district families are economically disadvantaged (82%), WSD can offer free lunches to all students through the National School Lunch Program.

School director Jennifer Lowman has served on the Cheltenham School District (CSD) school board since July 2020. She is currently a co-chair of the board’s Policy Committee, and she serves as her district’s representative on the Montgomery County Intermediate Unit (MCIU). Cheltenham Township is a suburban community in Montgomery County, PA, which sits on the northwest border of the city of Philadelphia. Although comparatively small with about 37,000 residents, Cheltenham Township is home to people of many different racial, religious, social and economic backgrounds. Like the township, CSD is highly diverse with a total population of about 4,200 students, 53.3% of whom identify as African American, 23.8% as white, 9.8% as Hispanic, 8.3% as multiracial and 4.7% as Asian. The district currently operates seven schools: four K-4 elementary schools, one 5-6 elementary school, one 7-8 middle school, and one high school, serving approximately 4,200 students. (This grade configuration will be changing next year, with fifth grade returning to the elementary schools, and sixth grade joining the middle school.) Also, 19.8% of CSD students receive special education services, and 29.8% of its students are eligible to participate in the federal free and reduced-price meal program.

School director Kelly White has served on the Wyalusing Area School District (WASD) school board since December 2021. She is currently serving as board president and on the following committees: Curriculum, Instruction and Technology; Personnel; Policy; and as the PSBA liaison. She has also been part of the PSBA’s nominating and bylaws committees. WASD spans approximately 250 square miles in rural northeastern Pennsylvania, serving students across Bradford and Wyoming counties. The district has a student population of roughly 1,300 students, with a demographic composition that is predominantly white (approximately 95%), with small percentages of Hispanic, multiracial and other minority students. The community surrounding the district has a median household income of about $62,300, slightly below the Pennsylvania state average, reflecting the area’s rural agricultural and blue-collar economic base. Also, 51.5% of students are economically disadvantaged. Despite its expansive geographical coverage, the district maintains a relatively low student-to-teacher ratio, allowing for personalized educational experiences across its elementary school and combined junior-senior high school campus. More information about the district can be found at www.wyalusingrams.com.